Driving into Clarksdale, MS is a bit like driving into the Great Depression era. The gas stations and fast food joints quickly give way to empty brick buildings with faded signs and logos. We stop in an empty lot to get our bearings. An older pickup truck pulling trailer pulls in and back up to a door at the side of the adjacent building. The door opens, greetings are exchanged and the men begin hauling out appliances and throwing them on the trailer, each appliance crashing onto the others. We are discussing how to get to the Blues Museum.

“It’s down this road few more blocks. Then turn toward the railroad tracks.” Lorraine says looking at the miniature map on the cell phone.

The pickup truck with its trailer mounded with white metal cubes pulls out on to the street and disappears around the corner. We follow, heading into town.

Well we have found it but there is no place to park and it doesn’t look like it’s open. Lorraine doesn’t like the feel of the place. I look around. There’s no one around except for three Black men working in the park across the street.

“I’ll go ask them.”

I walk across the street. They look up. One is holding a running weed trimmer.

“Excuse me.” I say to the biggest man who is apparently the de facto leader of the group, ”Can you tell me if the Blues Museum is open?”

The man holds his hand up to his ear.

Louder I say, “Can you tell me if the Blues Museum is open?”

The man looks at me, shakes his head and turns to the one with weed trimmer.

“Will you shut that damn thing off?” he bellows in a voice that could be heard over most any machine.

“I’m sorry sir. Could you repeat what you were sayin’?”

“Thank you, Yes. Can you tell me if the Blues Museum is open?”

“Well, to tell you the truth I cannot. We’re not from around here. Ya see, we’re the prisoners. Go ask that man over there. He’s free.”

“You mean you’re not doing this voluntarily?” I say pointing at the weed whackers.

“No sir, we are not!”

I go ask the free man who directs us down an alley which leads to the back of a bank and then to the parking lot. As I return to the truck I notice the 3 black men are all wearing the same striped pants.

Alan Lomax arrived here in August 1941. It is here that he learns from Son House that Robert Johnson is dead. Son suggests he look up an up and coming player named Muddy. “Go out to Stovall Plantation and just ask for Muddy. They’ll know who ya mean.”

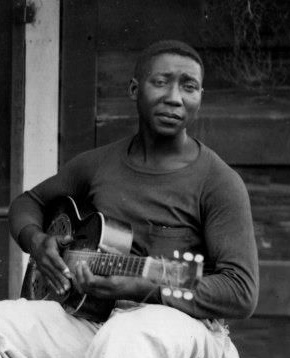

McKinley Morganfield was born in Rolling Fork in 1913 or 1915. No one is quite sure. His mother died shortly after he was born and he was raised by his grandmother as a sharecropper at Stovall Plantation near Clarksdale. His grandmother insisted he attend church and it was here he learned music in the Black gospel tradition. It was also his grandmother who gave him the nickname Muddy for his propensity to return home from playing along the creek covered in mud.

He began playing harmonica in his early teens and at the age of 17 sold the family’s horse. He gave half the money to his grandmother and with the other half purchased a guitar from Sears & Roebuck for $2.50. Soon he was playing the juke joints on Stovall Plantation and learning from the touring blues musicians who stopped by the Plantation. This was his life when Alan Lomax came asking for Muddy.

When Morganfield heard a white man was asking for Muddy he almost ran away thinking that they’d discovered he’d been selling whiskey on the side but he decided to stay and face the man. When he found out that Lomax wanted to record him he took him to his cabin and played by trunk of Lomax’ car into a recording machine. On hearing the recording played back he realized he could actually play music. “I can do it. I can do it.” He shouted gleefully. Lomax returned in 1942 and recorded a second session. That second session gave Muddy ideas. The following year he headed up Highway 61 to Chicago with the aim of becoming a professional musician. Along the way he adopted the name Muddy Waters and in Chicago he discovered something new, the electric guitar.

Working in a factory during the day and playing the clubs at night Muddy Waters saved enough money to buy an electric guitar two years later. It was in the Chicago clubs he developed a style and sound that would change music. By the early 1950’s he was the charismatic star of an electric band that displayed a mystical, sexual persona with songs such as “I Want to Make Love to You”, “Hoochie Coochie Man”, “Rollin’ Stone” and “I Got My Mojo Workin’”. The success of Muddy Water’s style was not overlooked by a skinny young white boy from Tupelo, now living in Memphis and looking to hit the tour circuit and make his mark.

In 1958 Muddy Waters toured Britain. In the audience were young musicians just starting out. Among them Eric Clapton, Van Morrison and Mick Jagger. Jagger would name his group after Muddy’s song “Rollin’ Stone”.

Here is Muddy Water’s 1955 recording of his song Mannish Boy.

Once we are inside the Blues Museum we are led to the one room cabin Muddy Waters grew up in. Nothing but boards nailed to a frame with newspaper glued to the walls to cover the cracks. It was impoverished sharecroppers living in quarters like this that developed a new and distinctly American form of music. Probably because no one had told then the right way to play music.

We leave Clarksdale on Highway 61 heading south, passing the crossroad where Robert Johnson is reputed to have made his bargain with the Devil. We are going on to Indianola to find the story behind the Kings.