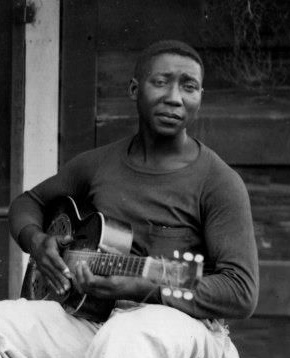

From Clarksdale south along 61 to Indianola where in 1948 a 23 year old black man named Riley King with a back ground similar to Muddy Waters’ is leaving sharecropping and the juke joints behind to seek his fortune in Memphis. Shortly after he arrives in the city he gets a job writing advertising jingles and occasionally performing on WDIA, Memphis’ all Black radio station. It is here he takes on the name B. B. King. Soon King is playing the clubs on Beale Street. It was here that King developed is trade mark sound backing up is guitar and singing with horns, saxophone and piano. He began recording in 1949.

1949 was the year RCA and other recording studios dropped the term race records for recordings marketed to Blacks. The new term for race targeted recordings would be Rhythm and Blues. B.B. King had his first Rhythm and Blues hit in 1952 with his 1950 recording of “3 O’Clock Blues”.

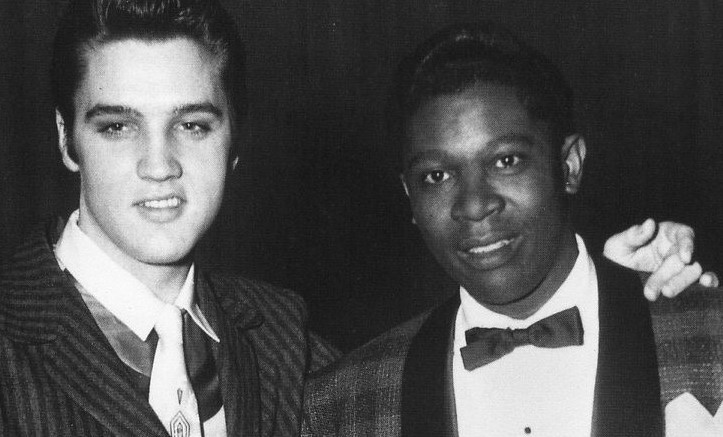

In 1953 Elvis Presley, a senior in high school, is frequenting Beale Street enamored of the flashy clothes of the bluesmen. It is on Beale Street that Elvis and B. B. King meet. King has already recorded 2 albums at Sun Records in Memphis. He suggests Presley might find work there. In August of 1953 Presley goes to Sun and pays for a few minutes of studio time perhaps hoping to be “discovered”. He records two songs on a single acetate disc which he gives to his mother. Sam Phillips, the owner of Sun, writes in his notebook “Elvis Presley, Good ballad singer. Hold”. Elvis is not “discovered” and gets a job driving a local delivery truck.

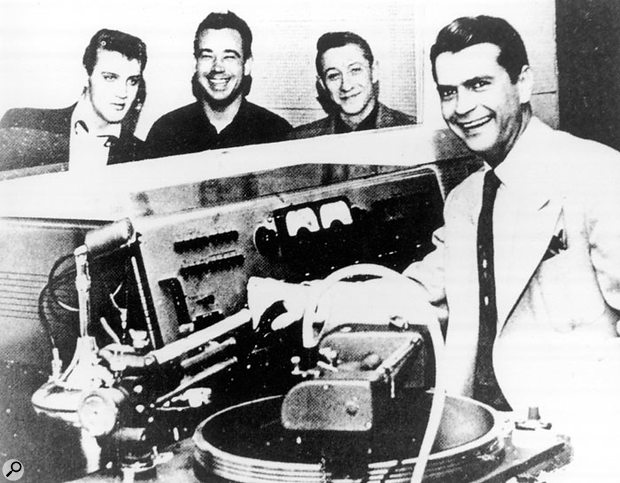

Sam Phillips continues to run his recording studio often telling people “If I could find a white man who had the negro sound, the negro feel, I could make a million dollars.” In June of 1954 Phillips invites Presley back into the studio. “Sing everything you know.” He says to Presley. After the session he asks Presley to come back in a week. He’ll be singing his songs with 2 local musicians backing him up.

Presley returns on July 5th and works with guitarist Scotty Moore and upright bass player Bill Black. The session was not fruitful. As they decide to call it quits Presley picks up his guitar and starts into the blues number “That’s Alright (Momma)”. Recalls Moore, “All of a sudden Elvis just started singing this song, jumping around and acting the fool. Then Bill picked up his bass and started acting the fool too, so started playing along with them.”

Sam Phillips sticks his head out of the recording booth and says, “I don’t know what you boys are doing but back up, find a place to start, and do it again.” He turns on the acetate recording machine. Two days later he’s delivering acetate copies of the recording to Memphis dj’s. Within days the questions are coming into the Sun Records studio. Who is this guy? Is he Black? Can I get him for an interview?

Elvis Presley’s career was launched. He was on his way to become the King of Rock and Roll but he didn’t forget his roots. In 1956 he returned to Memphis to see his friends and support WDIA the all Black radio station.

B. B. King would later say, “When Elvis appeared at the WDIA fundraiser for Negro children he was already a big, big star. Remember this was the Fifties so for a young white boy to show up at an all Black function took guts. I believe he was showing his roots and seemed proud of those roots.”

“All our [Elvis and mine] influences had something in common. We were born poor in Mississippi, went through poor childhoods and we learned and earned our way through music. You see I talked to Elvis about music early on and I know one of the big things in his heart was this: Music is owned by the whole universe. It isn’t exclusive to the black man or the white man or any other color. It is shared in and by our souls.”

For B. B. King the journey to stardom would take longer. In 1956 the South was segregated by law and the rest of the nation segregated by custom. By then King touring the so called chitlin’ circuit, a collection of Black clubs in the South that stretched from Atlanta to San Antonio. King had developed an interpretation of the Blues that featured himself backed up by a big band sound consisting of horns, sax and keyboard. He managed to acquire a bus to move the whole band from club to club. While Presley was staying hotels King had trouble finding a hotel that would allow Blacks. Often the band members rented rooms in Black family’s homes as no hotel would allow them.

Even the restrooms were segregated. King recalled how he would drive the bus up to a gas station and say to the attendant. “Put 100 gallons in.” As soon as the attendant lifted the gas pump nozzle he’d say, “Can I use your restroom?” If the answer was ‘Its out of order.’ He’d reply, “Never mind the gas. I’ll head down the road to one that is in order.”

But the miles wore on King. He was often on the road 300 days a year. He was popular among middle age Black audiences. He was making a living but he couldn’t expand his audience. Soul music had captured younger Blacks attention and Whites made up a tiny fraction of his audience.

Then in 1966 a promoter called from San Francisco. He wanted B. B. King to play the Fillmore. B. B. had played the Fillmore years before when it was a major dance hall in the Black section of the city but urban renewal and gentrification had changed the neighborhood. B. B.’s manager agreed.

In February 1967 B. B. King was backstage at the Fillmore waiting for the first band to finish. He took a peak between the curtains at the audience. He quickly found his manager. “I think we’re in the wrong place.” he exclaimed, “The audience, they’re White.” Yes they were in the right place he assured him.

“Then I started to get nervous. I’d never played before a White audience except when they had White night down on Beale Street. I decided to just do my best. When I walked onto the stage the audience was on their feet cheering and clapping for a full minute. There were tears running down my cheeks when I began to play. Well I guess we did alright because we got four standing ovations that night.”

He was on his way to become King of the Blues. There are no recordings of that concert. Here is a recording of a live concert in 1973 at Sing Sing Prison.

The Filmore concert changed B. B. King’s career. Before the bus could make it back to the chitlin’ circuit calls were coming in from venues in Chicago, New York and London asking if they could schedule the King of the Blues. He would go on to perform around the world with some of the biggest names in music. Before he was done he had performed for royalty, the Pope and the President, won multiple Grammy Awards, been inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

He became known as the Ambassador of the Blues for his willingness to help other musicians and his gentle kindly demeanor.

He continued to perform until a year before his death in 2015 at the age of 89. He was buried at the B. B. King Blues Museum in his hometown of Indianola, MS.

“The Blues? It’s the mother of American music. That’s what is is – the source.” B. B. King

Well that’s it. From Indianola we’re on to Vicksburg and Natchez. There the land is broken up by a series of bluffs and ravines and is no longer part of the Mississippi Delta region. A region that has had a powerful impact on American culture yet few take he time to explore it. Not only Blues singers but many important events in the early days of the Civil Rights movement occurred in the Delta. One could spend weeks exploring the region. We unfortunately only had four days.